ABSTRACT

This poster focuses on the most recent iteration of a design based research project which partners with community elders at a neighborhood museum in Nashville to develop digital-spatial story lines (Hall et al., 2019) made from collective (and evolving) archival material including video, oral history, and song. Using critical media literacy overlaid with situated learning, the current work uses interaction analysis (Jordan & Henderson, 1995) to understand how learners draw on resources related to listening in order to align personal and public histories, reinscribing experience through gesture and speech as they coordinate themselves within place and presence, contributing to the substrate of the street (Goodwin, 2017), ultimately developing powerful counter-narratives.

PROJECT BACKGROUND + PAST STUDIES

BRIDGING LEARNING IN URBAN EXTENDED SPACES (BLUES)

The Space, Learning, and Mobility (SLaM) Lab engages faculty and graduate students in design studies of how physical and virtual spaces can better support learning. Team members collaborate on research projects, design experimental teaching, and write about findings in the theme of learning on the move.

The BLUES project, funded by an NSF grant, is a design-based research (Cobb et al., 2003) effort spanning the last five years in partnership with a community museum on Jefferson Street in the historic North Nashville music corridor.

In the first phase of the project, the research team sourced materials original to the street’s history - maps, songs, videos, photographs, and other documents. These materials were digitized and associated with appropriate metadata inclusive of date, location, and other information as available. The repository of these digitized materials has been viewed in the context of our work as a digital media sand box. This sandbox has expanded as the iterations of the project have layered in oral histories and videos related to the work itself.

The early implementations of BLUES as a school-related activity series involved high school students creating “digital spatial story lines” (DSSLs), using source material from a combination of a physical sandbox (printed maps, newspaper articles, old photographs) and the digital one to tell a story about a particular day in Nashville’s history related to the civil rights movement, Nashville’s music history, sports legacy, and so on.

I have understood our work to be in the house of Social Design Experiment (Gutierrez and Jurow, 2018). Whatever design together, we hope we do make is taken up in ways that are sustainable and useful to community partners and learners.

Lorenzo Washington, owner of Jefferson Street Sound. photo: Eric England, Nashville Scene.

Students from Vanderbilt’s “Design Thinking Design Doing” class presented a concept for the museum space at Jefferson Street Sound.

Lubbock, H., Hostetler, A. L., and the Space, Learning and Mobility Lab. (2019). “History’s a myth”: Storytelling with youth to explore local history.” AERA

Hall, R. & Space, Learning & Mobility Lab (accepted with revisions). Here-and-then: Learning by making places with digital spatial story lines. Cognition & Instruction.

THEORETICAL CONTEXT

Situated learning

Learning is inherently social (Vygotsky, 1973)

Mind, culture, history, and the social world are “interrelated processes that constitute one another” and communities of practice are grounds for learning (Lave & Wenger, 1991)

Cognition is distributed between members and amongst social and physical environment (Hutchins, 1993)

Critical Media Literacy

Development from Critical Theory of the Frankfurt school, broadly seeking to “emancipate” (Horkheimer, 1982)

Then Critical Literacy Theory (Freire, 1970)

Examines social and political structures and systems of privilege and oppression (Kellner, 1995)

Looks to link issues of “ideology, bodies, power, and gender” in production of various cultural media artifacts (McRobbie, 1997)

Narrative Identity

Identity is story (Sfard & Prusak, 2005) and can be told as an artifact (Leander, 2017)

Perceived identity impacts learner outcomes (Larnell, 2016)

Identity and reality are socially constructed (Norton, 2013; Bruner, 1991).

KEY CONCEPTS AND TERMS

DEFINITION:

Wayfinding is the act of moving through places (wayfaring) and to places (transport) to experience them.

IN THIS STUDY:

This study positions learners to wayfind on Jefferson Street, moving along the corridor and to points of interest.

DEFINITION:

A counter map is a spatialized representation of a counter narrative.

IN THIS STUDY:

DSSLs are qualitative, thematic counter maps based on individual stories, related to civil rights, music, and history.

DEFINITION:

Ground-truthing is a way of testing a representation of a place against the on-the-ground experience of that same place.

IN THIS STUDY:

Where one normally aims to correct the representation, here ground-truthing is a practice to recontextualize past and present.

DEFINITION:

Narrative identity is a story that is told9 about who one is. The story is identity and can live as an artifact that shapes the way one sees the world.

IN THIS STUDY:

Where narrative identity is usually applied to persons, here we understand narrative identity as related to place - Heritage Park.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

What is the experience of wayfinding like for students following a digital counter map?

How do students narrate the identity of Heritage Park?

STUDY DESIGN

The BLUES Project has collaborated with a local museum and community leaders to collect a digital sandbox of original documents and oral histories about the Jefferson Street Corridor. We then designed a path in both Echoes and Storyliner, attaching similar content in each, for 13 master’s students to follow east to west, in small teams assigned to one or both apps. Students were transported from their university to the community museum. They then followed the path of the street, proceeding westward from the museum, toward an HBCU which marked the endpoint of the storyline

Echoes is a free app that automatically plays spatialized and geo-located sound in coordination with a user’s phone GPS.

Storyliner is our team’s in-house web app that locates digital media (videos, photos, playlists) on a map using clickable icons.

Consented students were randomly assigned one of three conditions related to the story-following tools: Echoes only, Storyliner only, or both Echoes and Storyliner. Students were then grouped in twos or threes by condition.

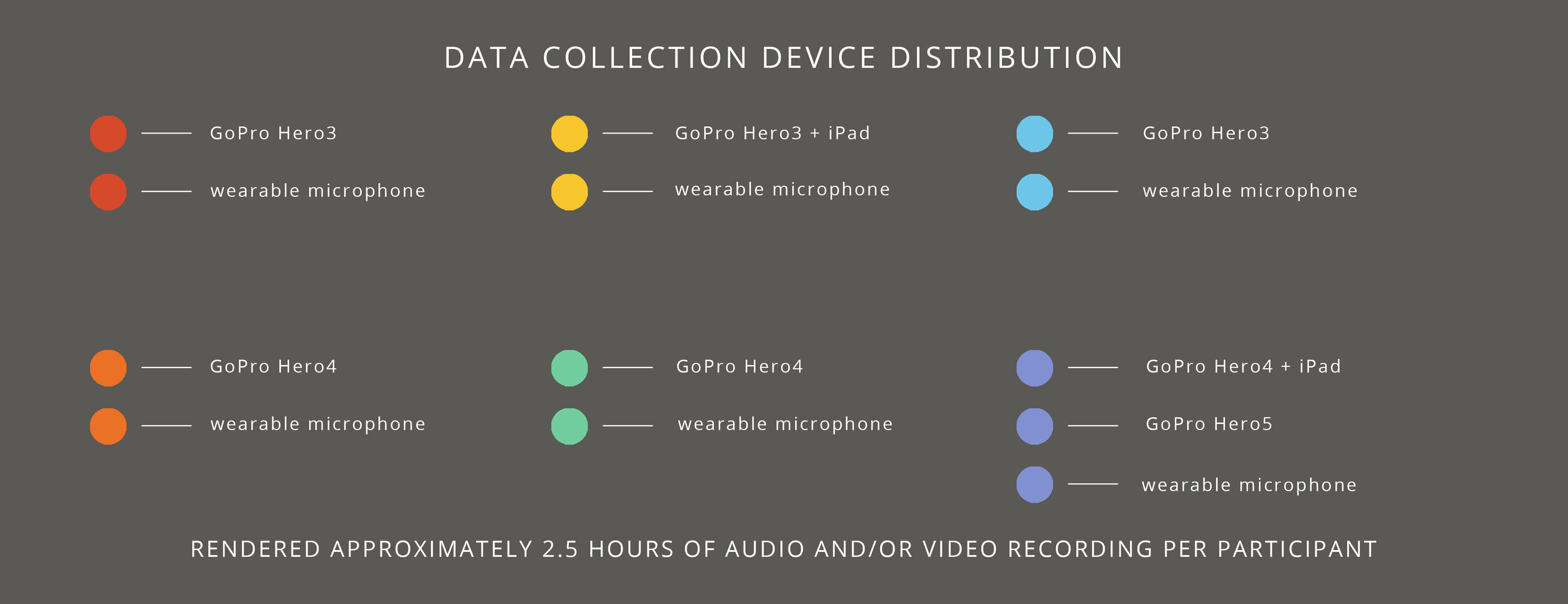

Data were collected while students walked down the street in form of video, screen-capture (on research team-owned devices only, not on students personal devices), and audio records of learners interactions with each other, the digital materials, and the physical environment.

one student in a pair wore a GoPro mounted to a CD jewel case worn around the neck to capture audio and video (and in some cases, topographical) information.

the other student in a pair wore a digital audio recorder (microphone)

if the pair is in a condition that uses Storyliner and has one of the research team’s iPads, then screen capture will be turned on for that iPad as possible.

Researchers staggered teams starting from Jefferson Street sound sending them toward TSU, sending one team every 3-5 minutes. Teams were sent in order of condition: Echoes, then Storyliner, then both. Researchers shadowed teams carrying a bag of charging cords, backup batteries, paper maps, and their interview guide.

When students reached the TSU campus, researchers accompanied teams, collected together into small groups by condition (all Echoes teams together, all Storyliner teams together, all Combo teams together). Researchers followed an interview guide to inquire about students’ experiences of the storyline following. Researchers carried a Vixia camera on a pogostick tripod to capture students’ interactions on the walk-back interview.

When we all reached JSS again, we stepped into the museum space for a question and answer time with Lorenzo Washington. Then, we’ll return to Vanderbilt and have mixed-condition and whole class discussions.

DATA ANALYSIS

Following the methods of interaction analysis (Jordan & Henderson, 1995), I selected cases of the audio-visual records that centered on a specific location along the walk, Heritage Park. I selected this site as a focus for narrowing cases (Derry et al., 2010) because it is an important landmark of the marginalization of this community and is an ambiguously defined space, one that begs sense-making.

Interaction analysis took place in a dedicated lab at Vanderbilt University where individuals from different projects and interests collect to assist one another in analyzing audio-visual records. Additionally, I brought one clip of the event to the participants themselves, testing a form of member checking merged with participatory research that would provide otherwise potentially absent insight for my analysis.

Following the sessions, I returned to the transcripts of the larger context of those interactive records, focusing on the walk-back interview portion, and coded for themes that emerged during the interaction analysis. I then selected cases across all three conditions that represented occasions when two major themes were at play: ground-truthing and narrative-driven place-making.

FINDINGS

DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS

The experiences of wayfinding (losing the way) and ground-truthing (minding the gap) build on one another, happening sometimes sequentially and sometimes simultaneously, necessitating learners’ own narration (filling the gap) to make sense of their surroundings. These encounter narratives at times align with a dominant narrative, other times align with the represented counter narrative in the map, and still other times manage to counter the counter map without subscribing to the dominant narrative. This draws our attention to the relative nature of counter mapping and demonstrates the diverse encounter narratives learners can develop in wayfinding with a counter map.

Encounter narratives:

demonstrate creative reuse with transformation (Goodwin, 2018) of past experiences, personal knowledge, and external media.

expands time-space context of the counter map through importing in and imagining out

show learners taking an active role in producing (De Certeau, 1998) the identity of the place in which they walk.

The encounter with the counter map (and its associated data collected) become, in essence, yet a new transect layer of narrative on the street. The instance of Torrey importing her memory of a classmate discussing Jefferson Street serves to show just how important the role of these encounter narratives is in shaping narrative identity of place and contributing to the substrate of place.

LIMITATIONS

• As the context was a formal learning setting, participants may have been “doing school”17, the effects of which could be embedded in our data.

• We noted students who felt they “missed” points of interest or “couldn’t learn” when an app didn’t work. The day-to-day experience of smartphone users may bias them to expect a certain finesse in using an app.

• These participants had a university education in social studies, so high school participants might have a different approach.

• Jesse and Lorenzo don’t build counter maps. There is an authority to mapping that is in this sense still not easily accessible to some in this community.

GOING FORWARD

We have an on-going effort to do a contrasting (where this was comparative) study of Echoes and Storyliner as platforms for counter maps. In coming design cycles, we intend to try new and expanded counter maps in the same apps with different participant groups. Some questions we have now:

• When, how, and why do people return to certain themes, ideas, or topics while learning on the move?

• How would populating a counter map with more and different counter narratives affect findings?

• We know from our design cycles that, if you’ve made a storyline or counter map, then you relate to someone else’s differently. What is that difference and how can we design for/with it?

photo: Ka:ren Wieckert

photo: Ka:ren Wieckert